Reverse Cervical Curve: The Final Stage of Forward Head Posture

By MADI-BONE CLINIC | Gangnam (Seolleung Station)

“This Is Not Just Tech Neck Anymore.”

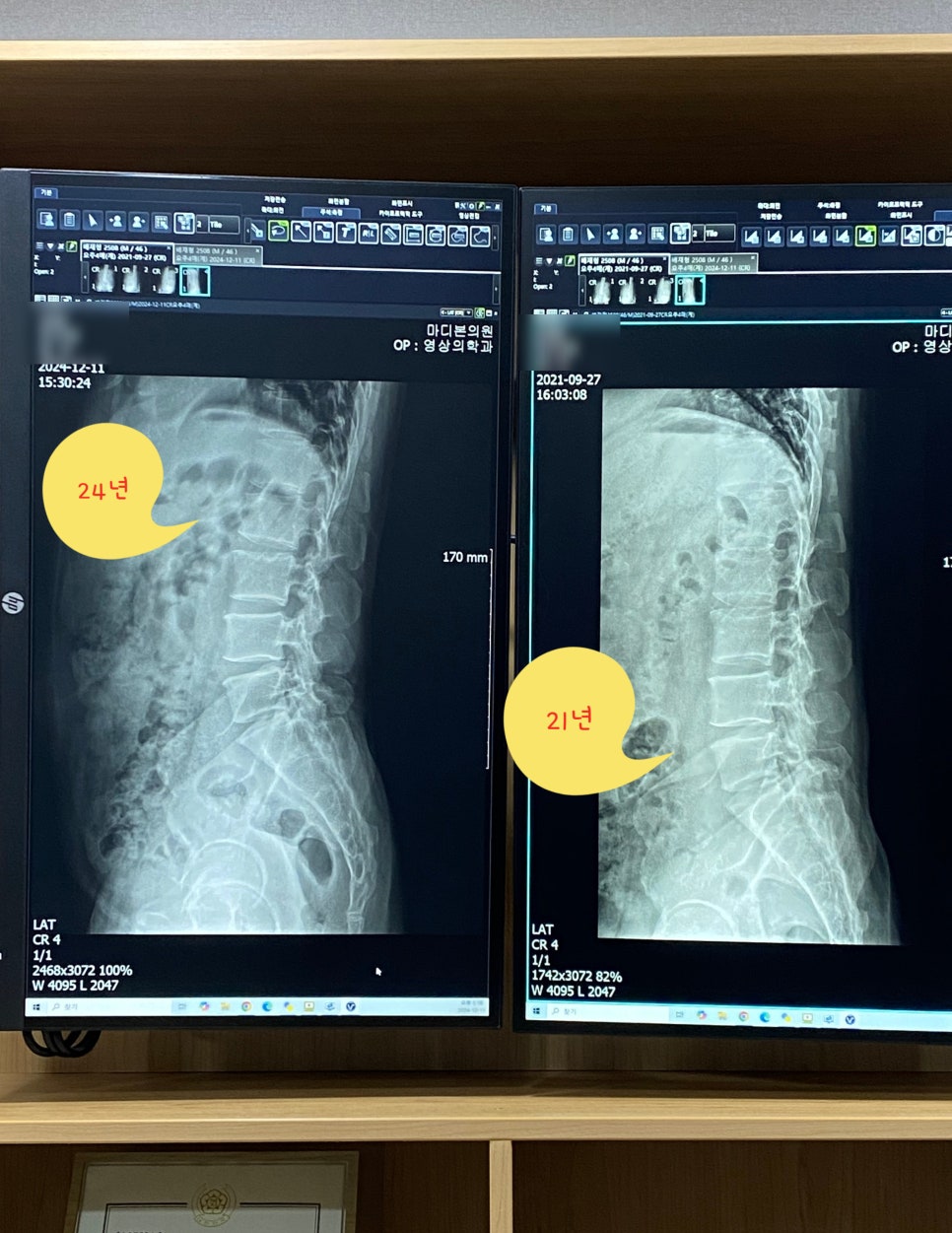

When we reviewed recent cervical X-rays from patients in our clinic, a surprising number already showed a reverse cervical curve — not just a straight neck, but a curve that bends in the opposite direction of normal.

This is no longer a simple forward head posture. It represents the final, most advanced stage of cervical alignment deformity.

From Normal Curve to Reverse Curve: The Progression

Cervical alignment usually changes gradually over time:

- Normal C-curve (lordosis)

Optimal shock absorption and the lowest muscle fatigue. - Straight neck (loss of lordosis)

Discs and facet joints begin to receive more direct load. - Forward head posture (FHP)

The head shifts forward, increasing muscle tension and headache frequency. - Reverse cervical curve

The curve is actually inverted. Structural changes are more fixed and harder to correct.

A reverse curve means the cervical spine has lost its normal C-shaped lordosis and has collapsed into a kyphotic or reversed shape.

Why a Reverse Curve Matters

1) Muscle and Ligament Overload

Without the natural C-curve, the cervical spine can no longer absorb forces efficiently. Shock is transmitted directly into the discs and facet joints, and muscles must work much harder just to hold the head up.

2) Higher Disc and Joint Stress

Biomechanical research suggests that loss of lordosis and kyphotic alignment increase mechanical stress on the lower cervical segments (often C5–C7), which may contribute to disc degeneration and symptoms.

Biomechanical analysis

3) Headaches and Trapezius Tightness

Overloaded cervical and upper trapezius muscles often lead to:

- heavy, tight pain around the neck and shoulders

- tension-type headaches, sometimes starting at the back of the head

4) More Difficult and Longer Correction

Compared with mild forward head posture or a simple straight neck, a reverse cervical curve:

- takes more time to correct

- requires more structured rehabilitation

- is more likely to relapse if maintenance is poor

What We See in the Clinic

We now see reverse cervical alignment even in patients in their 20s and 30s. Typical patterns include:

- chronic neck and upper trapezius tightness

- recurrent headaches that worsen with long study or work hours

- limited neck extension (looking up feels stiff and restricted)

- temporary relief with stretching, but symptoms quickly return

Many patients only realize the degree of their posture change when they see their own X-ray.

Three-Phase Strategy for Reverse Cervical Curve

A reverse curve does not improve with “a few stretches.”

We usually plan treatment in three phases:

Phase 1 — Pain Reduction

- cervical injections (nerve, facet, or trigger point) when indicated

- muscle relaxation and soft-tissue techniques

- medication support if needed

The goal is to reduce pain enough to allow active corrective exercise.

Phase 2 — Structural Correction (Key Phase)

- Deep cervical flexor (DCF) training — chin-tuck variations, low-load endurance work

- Cervical extensor strengthening — to support the natural curve

- Thoracic mobility restoration — improving upper back extension

- Scapular stabilization — better shoulder blade posture and endurance

- Ergonomic education — screen height, sitting posture, and regular breaks

Evidence supports combining exercise therapy and manual therapy for neck pain and cervicogenic symptoms.

Neck Pain CPG, 2017;

deep cervical flexor training trial.

Phase 3 — Maintenance and Habits

- regular physical therapy sessions as needed

- home exercise routines to maintain muscle balance

- long-term adjustment of work/study environment

This phase prevents relapse and helps improvements become “the new normal.”

How Long Does It Take?

Timeframes vary depending on degeneration, pain level, and muscle balance, but in general:

- Mild forward head posture: about 4–8 weeks

- Straight neck (loss of lordosis): about 2–3 months

- Reverse cervical curve: typically 3–6 months or longer

Recovery from a reverse curve requires a longer and more patient approach than early-stage posture problems.

When Should You Get Checked?

- persistent neck and shoulder tightness despite stretching

- recurrent headaches that seem to start from the neck

- a clearly visible forward head posture in photos or mirrors

- pain already interfering with work, study, or sleep

The earlier we diagnose and treat, the shorter the treatment and the better the chance to improve the curve.

MADI-BONE CLINIC (Seolleung Station, ~3 min on foot)

MADI-BONE CLINIC

3F, 428 Seolleung-ro, Gangnam-gu, Seoul

Seolleung Station (Line 2), Exit 1 — ~3 minutes on foot

02-736-2626

⏰ Mon–Fri 09:30–18:30 / Sat 09:30–13:00 (Closed Sundays & Public Holidays)

Sources (for Interested Readers)

- González-Sánchez M, et al. The relationship between head posture and neck pain (systematic review). Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2020. PubMed

- Kim EK, Kim JS. Effect of deep cervical flexor training on forward head posture and pain. J Phys Ther Sci. 2016. PubMed

- Blanpied PR, et al. Neck Pain: Clinical Practice Guidelines (Revision 2017). J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2017. PubMed

- Takeda N, et al. Cervical spine alignment and disc load (biomechanical model). PubMed

- Additional work on cervical kyphosis and symptoms: PubMed

This article is for educational purposes and does not replace an individual medical evaluation or treatment plan.